MUSIC: The role of ‘Take me home, country roads’ in Miyazaki’s Whisper of the Heart

By Laura Kee

With reference to secondary literature and musical examples from your chosen media, write an analytical essay using some of the following prompts for guidance: what is the effect of the music in terms of narrative / aesthetic / characterisation? To what extent is music’s role reliant on audiences’ prior associations of the music? To what extent has the music been transformed due to its use in the media that you chose, i.e. what Godsall calls post-existing music (2021)?

The scope of music in film today ranges from solely original composition to entire compilation scores of pre-existing material. Hayao Miyazaki’s Whisper of the Heart (dir. Yoshifumi Kondō, 1995) sits between these categories, featuring both an original score – composed by Yuji Nomi – and John Denver’s 1971 hit ‘Take me home, country roads’. The choice to include this song in the score is itself striking. Denver’s heartfelt homage to the United States and Virginia could not feel more incongruous with a coming-of-age story about a young girl in Tokyo, and the song is not only featured, but lies at the very heart of the film’s narrative. Studio Ghibli’s ninth feature film incorporates three full performances of the song, each substantially different in their sound. This essay will discuss how the relationship between the song and the film shapes the narrative of Whisper of the Heart, and how Denver’s American classic remains relevant within a work of Japanese animation. Furthermore, I will highlight how the involvement of this single piece of pre-existing musical material on an otherwise original soundtrack mirrors the story on screen and blurs the line between narrative and soundtrack.

The first use of the song in the film plays a crucial role in both the scene and the wider narrative. Olivia Newton-John’s 1973 cover of the track is what introduces Miyazaki’s picturesque vision of Tokyo, a typical music-to-montage setting of scene. Nevertheless, Denver’s ode to West Virginia is undeniably a deviation from the studio’s norm. The vast majority of Studio Ghibli’s soundtracks follow Claudia Gorbman’s seven principles of narrative film music (Claudia Gorbman, 73). Her argument that ‘most feature films relegate music to the viewer’s sensory background, that grey area of secondary perception least susceptible to judgement and most susceptible to active manipulation,’ (Gorbman, 12) holds true for much of Ghibli’s catalogue. As this narrative progresses, however, and protagonist Shizuku Tsukishima experiences the growing pains of balancing high school entrance exams and pursuing her passion for writing, and the sense of belonging that ‘Country Roads’ evokes gains narrative relevance. Furthermore, how distant Shizuku currently feels from that belonging becomes apparent. The song effortlessly pushes the narrative in that this sense of belonging is quite literally foreign to Shizuku. John Denver’s American lyrics and experience are inevitably incongruous with the everyday of a teenager in Tokyo. The role of the song in the film’s first act encapsulates this protagonist’s inner conflict; between translation difficulties and her own lack of confidence, Shizuku’s own diegetic reworking of the song is symbolic of her own doubts. The version that her and her friend sing at 8:30 is not only lacking in emotion but played off as a joke. This fragment of the song that is revealed first is an unsure parody and cannot yet stand alone. Despite this, it is symbolic of the beginning of Shizuku’s journey; the first of many diegetic features of the tune as it, and she, grow.

In her analysis of the music of Moulin Rouge! (dir. Baz Luhrmann, 2001), critic Jennifer Lauren Psujek remarks upon Luhrmann’s frequent use of Elton John’ ‘Your Song’ and keeping the song ‘recognizable without exactly mimicking the record’ (Jennifer Lauren Psujek, 210). ‘Country Roads’ receives similar treatment in Whisper of the Heart. Its role in the narrative alongside its place on the soundtrack results in frequent references, even though the song only plays in its entirety on three occasions. The a capella fragment of the song that introduces Shizuku’s re-write is the closest to the original. Regardless of the language change, this excerpt is just the unmistakable ‘Country Roads’ melody. As the film goes on, both the song and Shizuku herself grow into themselves as individuals. What began as a curious song choice to open the film asserts itself instead as a theme to Shizuku’s coming of age. Kondō, Miyazaki and Nomi ‘re-arrange and re-orchestrate […] in order to intimately fit the cue to the images’ (Psujek, 211) and mirror and propel the narrative through sound. This can be observed further through the song’s second full feature at 55:10, a diegetic performance by Shizuku and love interest Seiji Amasawa. Seiji’s violin starts the song, immediately making it more distinctive and quirkier than before while still maintaining the melody that makes it so recognisable. Once again, the song holds significance in direct relation to the narrative. The couple’s new-found bond and ways of inspiring each other bring new life to ‘Country Roads’. Although the first full performance of the song was non-diegetic, this re-worded and re-orchestrated version placed in direct comparison to how the film began reflects the story told thus far in that a new sense of identity is forming for both Shizuku and the track itself.

This vastly different second performance of ‘Country Roads’ has implications beyond the narrative, however. As well as characterising the growth of the film’s protagonists, the song itself is transformed. Among new instrumentation – violin, recorder, cello and what closely resembles a bouzouki – the melody is all that remains of the original. The growing distance between Denver’s beloved classic and Shizuku’s interpretation inspires the question of whether ‘Country Roads’ has outgrown its roots through the film. Jonathon Godsall’s study of pre-existing music from within narrative films explores this concept. His reminder that ‘the production and reception of films and their music do not occur in a vacuum’ (Jonathan Godsall, 9) opens up the question of what happens to pre-existing music when it crosses the bridge into an unfamiliar filmic context. Pre-existing music in this setting simultaneously cannot completely discard its prior associations, but also has no control over how it is interpreted and heard by new audiences. Hence, here, John Denver’s authorial intention is redundant, despite the song being his own work. Godsall suggests that ‘pre-existing music is, uniquely, music changed by its filmic appropriation; music with both a ‘before’ and ‘after’ in the public sphere,’ (Godsall, 163); Whisper of the Heart goes a step further, rearranging a track to fit within a new culture as well. Interestingly however, ‘Country Roads’ was not only a well-established song in Japan, but Newton-John’s cover went onto peak at number six on the Japanese music charts (perhaps even the reason why her version of the track was chosen for the film, and not Denver’s). ‘Country Roads’ undoubtedly had its ‘before’ time in the public sphere of Japan, but with a change of lyrics and striking new instrumentation, the film offers something that feels altogether new. Based upon this, an argument could be formed around Godsall’s concept of ‘post-existing music’ in relation to this example – that ‘our understandings of music can be changed’ through how the film and music interact (Godsall, 163). I would suggest however, that the understanding of ‘Country Roads’ that Whisper of the Heart projects is not markedly different from Denver’s original.

The song itself is undoubtedly reinvented through Whisper of the Heart. The changed instrumentation alone demonstrates this: the country sound of finger-plucked guitars that are a staple of both Denver’s and Newton-John’s versions are completely absent. This re-birth of the song in a new context, however, embraces its prior associations, using them to grow further rather than forge new meaning. The unlikely harmony between a story of a girl in Tokyo and Denver’s patriotic call to his home in the United States convey a similar message. ‘Country Roads’ is so effective at pushing the film’s narrative because of this surprising similarity. Godsall is not wrong that when put in a filmic context, pre-existing music inspires new understandings, but Whisper of the Heart is not an example of what he names ‘post-existing’ music. Both the ‘before’ and ‘after’ of this song are about belonging. Whether that be belonging to a physical place (West Virginia) or discovering a new belonging through growing up and understanding yourself better – ‘tomorrow, the me I always am, I want to go back, but I can’t, farewell Country Road’ (translated lyrics, Whisper of the Heart, 1995). Shizuku best explains this at 36:20: ‘I don’t know about old hometowns, so I wrote about what I feel’ (1995). The geographical specifics of Denver’s lyrics are not something universally understood, but the emotion behind them, the desire to belong, could be sung by anyone. Rather than redefining a piece of pre-existing music, the film nurtures the history of the song and invites audiences to revisit and expand upon its initial meaning. In this respect, the impact of ‘Country Roads’ within the film is tied to prior associations of the song, yet not dependent on them.

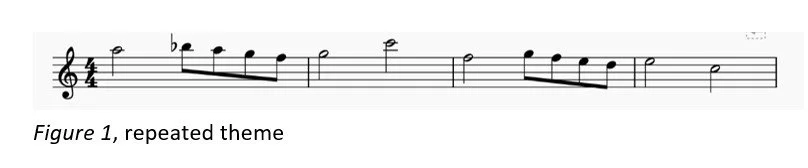

What makes Whisper of the Heart noteworthy is its soundtrack. Unlike the ‘blended composite score’ (Psujek, 3) – the term Psujek uses to describe soundtracks featuring both original and pre-existing works, ‘Country Roads’ is the only pre-existing piece of music on the film’s soundtrack. Yuji Nomi’s original work for the score functions similarly to the classical Hollywood scoring; there is an unmissable leitmotif appearing frequently throughout the film’s second half. First appearing in ‘Flowing Clouds Atop the Shining Hills’, this short theme (see figure 1) then features in five further tracks in alternate forms.

The simple melody is re-imagined and repeated in an array of styles: it is slow and sweet on the flute and violin in ‘Canon’, then in a minor key with an unsettling new pace in ‘Forest of Anxiety’. Nomi’s score mimics the emotion on screen just as a classical style score would. Hence, ‘Country Roads’ is inconsistent with the rest of the soundtrack. It does not attempt to mirror specific moments in the story, but rather plays an active narrative role. The contrast between how the song opens the film and ends it is striking, as narratively it develops from a whimsical school project to a symbol of belonging and progression. This is shown musically through the blending of the final performance of the song into Nomi’s original score. What began as distinctively separate from the rest of the non-diegetic sound of the film eventually finds its place within the soundtrack, with an oboe playing a fragment of the melody of ‘Country Roads’ within another track at 1:30:38. Most notable, however, is the transition between the final two tracks, ‘Crack of Dawn’ and ‘Country Roads’. This final version of the song is seamlessly blended, the sound and continuity not breaking once between the two tracks, and it is finally congruent with the rest of the soundtrack. Whilst still clearly recognisable as ‘Country Roads’, this final performance is the most musically removed from Denver’s original. The isolated ‘country’ sound of fingerpicking is replaced with the piano, strings and synth that characterise Nomi’s soundtrack. Most importantly, it is Shizuku’s original translation and voice featured in this final performance. Narrative closure is achieved through the protagonist’s non-diegetic affirmation of growth.

The relationship between ‘Take me home, country roads’ and the story is at the very core of Whisper of the Heart. This hugely popular pre-existing track takes on a new life as the theme to Shizuku’s coming-of-age, translating Denver’s universal message of belonging into the filmic context. ‘Country Roads’ serves a distinct function throughout the film; as a recurring feature of the narrative, it brings shape to the story as well as mirroring Shizuku’s personal journey in its ongoing changes. Moreover, Kondō’s handling Denver’s classic transforms the song without dismissing its history. Whisper of the Heart acknowledges and builds upon the sense of belonging behind Denver’s lyrics, and its place within the narrative honours its past success. The re-invention of ‘Country Roads’ is at the forefront of the narrative, and yet is never beyond recognition. Despite its history and American roots, ‘Country Roads’ succeeds in communicating the heart-warming message of belonging found within the heart of Whisper of the Heart.

Bibliography

Primary sources

Kondō, Yoshifumi. Whisper of the Heart, Hayao Miyazaki, Studio Ghibli, 1995.

Luhrmann, Baz. Moulin Rouge!, Bazmark Productions, 2001.

Secondary sources

Godsall, Jonathon. Reeled in: Pre-existing Music in Narrative Film, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018. pp. 9, 163.

Gorbman, Claudia. Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music, The British Film Institute, 1987. pp. 12, 73.

Psujek, Jennifer Lauren. “The Composite Score: Indiewood Film Music at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century.” PhD dis., Washington University, 2016. pp. 3, 210-211.