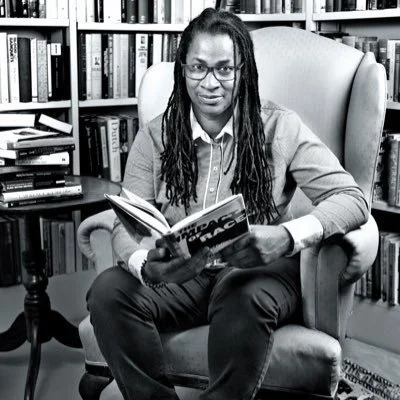

Interview with Lennox Goddard, Department of Drama, Theatre and Dance

Lennox Goddard is Professor of Black Theatre and Performance. Their research and teaching is focused in the area of the politics of contemporary Black British theatre and performance, including work on new writing by Black playwrights and contemporary Black productions of canonical plays. Their research on Black theatre practice also includes exploring debates about race and casting in contemporary Black British productions. They are interested in hearing from students researching areas relating to race, intersectionality and performance, Black theatre, and/or womxn's theatre and/or LGBTQI* theatre.

In this interview, we discuss Lennox Goddard’s piece, ‘Street Life: Black Masculinity and Youth Violence in Roy Williams’ ‘Urban’ Plays’, which is in part two of Contemporary Black British Playwrights: Margins to Mainstream. Lennox explains their inspiration for becoming an academic and gives some insightful advice on finding your passion when writing, and we discuss some staggering statistics on the diversity of academics in the UK.

ISOBEL: Today, we're joined by Lennox, who is going to answer some questions about their piece. Do you want to start by introducing yourself, your academic focus, and then explain a little bit about what your featured work was on?

LENNOX: So, I'm an academic. I've been here at Royal Holloway since the late 1990s, and ever since the start of my career, I've been committed to documenting and analysing contemporary Black British theatre.

In the beginning, that was mainly about writing about plays and their productions, and also kind of answering questions around Black theatre as a political practice. It's emerged now into Black theatre as an activist practice. So I'm very interested in the ways in which those plays and Black plays by British born writers, explore aspects of our identities, our experiences in the UK, and so I focus a lot on kind of social issues that Black playwrights will deal with. In my first book, I was looking at Winston Pinnock and thinking about the ways in which her plays dealt with migration, and also I looked at Black lesbian identities and Black queer identities. I was very much interested in the question of “what does a Black feminist theatre practise look like?”And by the end of doing that book, I'd realised that Black theatre had kind of turned a bit of a corner, and that playwrights were not so much concerned with identity politics anymore. They'd moved on, and they were much more interested in the social issues that people were facing. So, this second book, Contemporary Black British Playwrights: Margins to Mainstream was really picking up on how we might analyse and interpret and understand the role that Black plays play in debating these issues. So, I had a range of issues and a range of playwrights.

It also had come from the fact that I noticed at that point that there was a sudden increase of black British work in the mainstream theatres in the UK.

Prior to the early 2000s, most Black British work that we saw was happening within small scale, mostly touring theatre companies in town and around the country. In the early 2000s, we had a moment where, suddenly, we were seeing Black plays in our main theatres.

Those really quite significant new writing venues in London, and what we saw in tandem with that was a rise in certain kinds of themes that would be an experience. One of my key themes was urban social violence. I looked at Debbie Green's work in terms of the way that she engaged in global agendas around race and racism to Kwame Kwei-Armah’s National Theatre trilogy. He had three plays on at the National Theatre over a period of about four years, which is quite significant really. So I looked at that trilogy and explored what that trilogy was doing… Roy Williams in terms of the urban, but also Roy Williams writes quite a lot about sports. And he writes her quite a lot about race, nation and sport. So I kind of divided that up to think about how sport allows us our national identities, I suppose, and how his plays invite audiences to think about the challenges of Black people in relation to notions of Britishness. And then I looked at Bola Agbaje as well, who was at the time, a young new playwright whose work was a bit more within the identity politics scheme, but also intersected a lot of the other themes that I was discussing. So yeah.

MIEKE: Thank you. Can you go into a bit more detail about your career as an academic writer, what got you into it, and specifically the field of Black theatre and performance?

LENNOX: Wow, where do you start with something like that! What got me into it? I was in my second year of my undergraduate degree when I did a course about theatre directors, and at the end of the course we had to write a 6000-word essay, which as a second year felt quite substantial! And on the course, I felt like we didn't really learn enough about Black directors or women directors. Actually, I think the only woman we did was Ariane Mnouchkine. Apart from that, we had done lots of men. My career prior to coming to university was as a Stage Manager. I had worked with a lot of Black theatre companies, and I knew that a lot of these companies were being run by Black women. So when I had to confront my 6000-word essay, I decided to write about about two Black British women directors whom I felt had slightly different styles. So, Yvonne Brewster and Denise Wong. Yvonne Brewster ran Talawa theatre company, and Denise Wong ran Black Mime theatre company. When I was writing this essay, it occurred to me that the history of Black British women's theatre at that time had barely been documented. So, I kind of set my task to document this work, to find a way to make sure that there's a history and a record that the work has happened. The other thing that I discovered when I was writing that chapter was that where Black women's work had been written about, it was written about as a feminist practise. So, there were two chapters in two books that documented this, where both were books about feminist theatre, and both seemed to suggest that the work was feminist. And what I discovered was that someone like Yvonne Brewster said, “well, actually, feminism hasn't got anything to do with my work. I'm a Black woman. I'm from Jamaica. I'm from a matriarchal society.” Feminism. That's the definition for white Western women.

So that tension became something that really interested me. It really made me think, OK. So, if the white academics are saying it's feminist, but the Black women practitioners are kind of distancing themselves from feminism. There’s a gap there that I might insert myself into and explore.

What does a Black feminist into practice look like? So, that was my PhD, which then became about this question of what is, what is Black Women's theatre? What's the difference between Black women's theatre and Black feminist theatre?

Why specifically Black theatre performance? Well, partly because no one was doing that work, not in any substantial way, right. There was a couple of essays at that time. And for me, it's specifically Black British theatre performance as well because there is a much larger raft of work on African American theatre. I’d come out of the industry. I'd worked in the field. I kind of knew the field a bit, but maybe it was just to document it. The next generation needs to know. In three generations time, needs to know that this work happened and what kinds of things those people were interested in.

ISOBEL: Thank you. What inspired this particular piece of work and how did you approach the writing and the research of it?

LENNOX: So, this was my first book. It was the first book that I was writing without the support of a supervisor. What inspired it, I think the first thing was that I was spotting the cultural debates about this moment in 2003, where we suddenly had a whole raft of Black British plays produced within the same year and people were kind of talking about this moment as a cultural renaissance. The second thing was, in 2003, I was finishing my PhD and I remember that there were two plays by Roy Williams and Kwame Kwei-Armah that were on within a couple of months of each other. Roy Williams's Fallout was being extended at the Royal Court while Kwame’s was playing at the National Theatre. So that was the first thing. The other thing that happened in that year was that Debbie Tucker Green emerged. She also had two plays on within a couple of months of each other. Dirty Butterfly was on at the Soho Theatre in February and then by the May they showed Born Bad at the Hampstead. That gave me a sort of historical moment onto which to pin my writing. What was it that was happening around the 2003 period that could account for this sudden upsurge in Black British plays on the mainstream? That was the first thing, the second point was also around the content of some of those plays. Both Roy Williams's play and Kwame’s were about young Black boys and street/urban violence, and the opportunities for young Black men to make it in British society. Both of them seem to be carrying that theme. And what I then discovered was that a lot of the plays by Black playwrights that would be introduced in mainstream venues were along this urban theme.

My first position, I suppose, was to criticise that. We've finally got a mainstream presence but it's with images of young Black boys wearing hoodies, bouncing basketballs, and thinking about whether they're going to deal drugs or not, and often dying, either at the beginning of a play or at the end of a play. There's a problem with that! My starting point was that there's a problem of what we're seeing in mainstream theatres. And then I decided to write a book to explore whether there's a more positive way of thinking about what those plays do, what they do as social documents of a moment in time, what they do to encourage audiences to think about the issues that young Black men are confronted with. Yeah, how we can look at them in a more positive way, you know, let's not just dismiss them because they exist. Let's think about how we can use them as tools for debate in our society. And then that broadened into some of the other issues that I already mentioned.

With researching and writing it, my first thing is to kind of read the plays. It always it starts with the text because in years to come, the text is what's left behind. So, the first thing is starts with the text. If I've seen the plays, I will have my notes that I will have taken when I've seen the play that I write into the text, and at a particular moment on stage. How did the audience respond at any particular moment? If I haven't seen the play, which for some of those, as I've said, it was 2003, I missed a lot of theatre that year. Then one of the really important things for me is to go back to the reviews. We've got a wonderful resource here called the Theatre Record. There are hard copies in the library up to a certain point, and then you can get it through electronic resource as well. If not here, then through Senate Library. I'll go back to the reviews in London Theatre records. I used the reviews to reconstruct the performance. What did the reviewers say was important about this performance? How does what the reviewers say keen to my thinking about the significance of an urban play? And then the last thing I did was read around the sociology of some of the issues that I explore. I'm thinking mainly female sex tourism in one of Debbie different Queens plays. I read a lot of the academic scholarship on what it means to have white women go into the Caribbean to enter into relationships with the Caribbean men. I read the kind of critical discourse and that and then I guess mapped it onto my reading of the plays, it kind of informed it, yeah. And also, I read, of course, other academic drama criticism on that.

MIEKE: What did you want to achieve when you worked on this piece?

LENNOX: I guess I said it already! I wanted to document plays at the time. I wanted to create the terms of debate through which we might understand this body of work.

I wanted to ensure that people recognise Black theatre as a genre in and of itself. I want people to kind of think about what the patterns in Black British playwright are in that 10-to-13-year period. The patterns of Black British playwriting from 2000 to 2013 are so different to the patterns from 1980 to 2000.

Also, the ways in which Black plays fit into the genre of British theatre more broadly. British theatre at that time was also dealing with political issues in terms of exploring social realism. “In your face” theatre had come about and I wanted to explore Black theatre through some of those questions that were being asked of in white British theatre. I wanted to put Black British theatre on the map!

ISOBEL: There’s a massive research gap in that obviously, and you'll fill in that, which is just really cool! Yeah… How would you say that your writing style has changed in terms of your writer’s voice since you've been writing and teaching?

LENNOX: I mean, I was wondering if it has changed. I'm an historian, so I think about myself as an historian, so I think about myself as first and foremost with documenting and analysing. I guess when I was doing my PhD - but that's the nature of a PhD -I was probably more theoretical than I am now. This book is not a theoretical book. It's a book that's about analysing plays and documenting those plays. The theoretical stuff that I bring to bear on this writing is just knowledge about the topic that's being discussed. So I would probably say that my writing is slightly less theoretical than it was? I don't know. I think I'm more confident in the tools that I'm bringing to an analysis now. I would do what's in the script, I would do what’s in the reviews. I don't know if my writing has changed a whole lot to be honest. I think the topics have changed, you know. So now I think much more around activist performance than maybe I did even in this book. But I don't know if it's changed or not.

MIEKE: As someone who's been in academia for a while, what do you wish you had known at the start of your studies that you know now? And within that, what advice would you give to undergrads?

LENNOX:

The one piece of advice that has helped me out over the years and I try to share it with everyone whenever I can is, I learned about the “bird by bird” approach to writing. Can I? Can I indulge this anecdote?

ISOBEL: Go for it! Yeah!

LENNOX: Bird By Bird is a book by Anne Lamott. At one point when I was doing my PhD, I got quite a bit of writer’s block. I was wondering whether I was ever going to be able to finish this PhD and I discovered this book! This book starts off with an anecdote about her brother who had to do a project on birds. He had the whole summer to do it. It's due tomorrow and he's sitting at the kitchen table with an empty piece of paper and he's tearing his hair out. One of his parents said. “You just have to do it, bird by bird.” So, you have to draw a bird and then you'll have a bird, and you draw another bird, and you’ll have two birds. She uses that to describe an approach to creative writing where she talks about giving the time to the project and allowing the creativity to happen. That means that if you set aside the time, say you’ll write between 10-12 today, 2-3 tomorrow… And you just sit at your desk, and you allow the words to come out. And I’ve used that approach ever since. That’s the one bit of advice I’d give to people. My thing is that you've got this project, and you divide your time up, you stretch your time up and then you stick to your commitment. If you're going to say you're working on the project between 10:00 and 12:00 on Tuesday, you go to your desk and you work. You work on your project. That might be writing, that might be reading, but whatever it is, you're putting your headspace into your project.

I guess the other thing that helped me with the researching of it was that I researched it chapter by chapter. So, I wrote the introduction last, but I researched it chapter by chapter, and so that would be another bit of advice I would give to people. When you've got a big thing that you divide it down into manageable bits.

I didn't know that I could write a book in four years, that's for sure! Which actually is not that long.

ISOBEL: Something that I thought i was really interesting… I had a look, did some research myself and I found out that only 1% of UK professors identified as Black in 2021 and I was just wondering, do you feel a certain pressure when it comes to writing as a person who isn't as well represented in your industry? And what advice would you give to aspiring academics who are people of colour?

LENNOX:

I think it's 61 now, Black women and AFAB non-binary professors in the UK at the moment. I think it's 61. When I became a professor in 2019, I was number 26, and that was 26 out of 20,000 professors in the country. So, 61/20,000 is still not great.

Some people would say that that creates a burden of representation. There's that kind of sense that as a Black person, you've got to write about Black stuff. And there are some people who would resist that they would be like, I don't want to feel that I've got to write about that stuff because I'm Black.

I just want to write about whatever. I don't feel it as pressure or as a burden of representation. Before I came back to university - I came back to university as a mature student - I was working in the Black theatre sector. That's where the jobs were for Black people at that time. After becoming an academic, I want to ensure that I document that work. I feel it as a responsibility, but not in a negative way! It’s really important that I speak about it. If I don't speak about it as a black person, then we might only hear about it from white people speaking about it! So, I think it's really important that my voice is in the discussion of Black theatre in Britain. And I am working on British perceptions of African American Theatre at the moment, and I think it's important that my voice is doing that too. I feel it as a pressure, and there are still not many Black, British or even black theatre scholars in the UK really.

Really, what advice would I give is to just do it! No, really. We need more voices in theatre, in academia. Across academia, of course but in theatre academia.

ISOBEL: Absolutely, yeah.

LENNOX: And I guess the other thing would be to kind of stay true to what you think is important. There could be an argument that some of my work is, I don't know, a simplified analysis of a few plays, you know. But for me, it's like, well simplified analysis of a few plays means that we start to talk about those few plays, and I’ve stayed true to that all through my career. It's Black theatre. It's Black British theatre. And that's what's important to me. So, I think it's about finding the thing that's important to you, and I mean, if you're talking about people that are entering into academia, I suppose you have to find a gap. You know, when I started the, the gap was there! There were two essays and now there are about three or more books about black British theatre, maybe a few more.

So yeah, it's about finding your gap, finding what people aren't saying, about the thing that interests you, and sticking with that!

ISOBEL: Definitely. And just before we finish, I just want say that if you want to look for any more works by Lennox, the publishing name is Lynette Goddard. Is there anything else that you want to add about your work or just your career in general?

LENNOX: It's been quite a long career. I didn't know I would have such a long career in academia. Yeah. Black plays matter!

ISOBEL: Absolutely. Yes! Well, thank you so much.